"The Stuff That Dreams Are Made Of" ... Bogart, Shakespeare, The Maltese Falcon, Those Great Movies

Saturday, April 30, 2011

Haiku Competition -- Entry #3

Rochester's tortured soul and Jane's unwavering spirit gave Orson Welles and Joan Fontaine two of the best movie roles of their careers. A moving tale of life's cruelty and love's redemption, worthy of poetry...

A pitiless world...

Passion denied...oh, Jane, Jane...

She hears his voice call...

*Jane Eyre (1944)*

This is an entry for the Best For Film Hollywood Haikus blogging competition. Enter now.

Friday, April 29, 2011

Haiku Competition -- Entry #2

I'm trying my hand at a little different type of haiku this time -- well, a lot different. A tribute to my favorite, absolutely awful movie:

Worst movie on screen...

Cardboard props, poor dead Bela...

What? No sequel? Aww!

*Plan 9 From Outer Space*

This is an entry for the Best For Film Hollywood Haikus blogging competition. Enter now.

Thursday, April 28, 2011

Film-Inspired Haiku Competition - My First Entry

Best For Film movie blog is sponsoring an unusual and challenging contest. Contestants must write a haiku-style poem inspired by the movie of their choice. The form of haiku consists of 3 lines of poetry -- the first line of 5 syllables, the second of 7 syllables, and the 3rd of 5 syllables. Multiple entries can be submitted. This is my first shot at a movie-inspired haiku:

Phantom love, so real,

Magic casements, misty seas,

Goodbye, m'darlin'....

*The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, 1947*

This is an entry for the Best For Film Hollywood Haikus blogging competition. Enter now.

Thursday, April 7, 2011

Mobsters, Pals and Skirts -- The Golden Age of Gangster Movies -- The Complete Series -- 1930 Through 1949

|

| Edward G. Robinson |

|

| Humphrey Bogart THE ORIGINALS THE BIG FOUR ROBINSON, CAGNEY, BOGART, MUNI Some have been as good, but no one has ever surpassed them. |

|

| James Cagney |

|

| Paul Muni |

Prologue

Why do we love the old gangster movies? I’ve never seen a gangster in my lifetime that was anything close to the handsome, colorful, well-dressed movie mobsters of the 1930’s and 40’s. The truth is that Al Capone, Busy Siegel and Lucky Luciano were no different than the sociopathic, predatory, drive-by shooting monsters we have today. I think that we love the old gangster movies, and the gangsters themselves, because although they depict violent events by murdering men, there is never a drop of blood, the gangsters are almost child-like in their desire to look rich and be part of high society, they speak in amusing accents, and they are played by incredibly charismatic, strikingly appealing men. They speak in colorful language – guns are gats, rods, heaters; women are skirts, dolls, tomatos; policemen are coppers, bulls, flatfoots. I believe it is also because there is an element of safety in the fact that these movies are of a long-past era, the true horror diffused by the cloaking veil of black and white film.

|

| Humphrey Bogart and Ann Sheridan, two great gangster movie favorites |

The Big Three are the original talkie gangster movies released from 1931-32. First to be released was Little Caesar with Edward G. Robinson, January 25, 1931. Second was Public Enemy with James Cagney, April 23, 1931. Both were products of Warner Brothers. Another studio slipped in there, however, with one of the Big Three – Scarface with Paul Muni, released April 9, 1932 by United Artists, produced by Howard Hughes. Scarface was actually the first movie made – it was filmed in early 1930, but release was delayed for 2 years because of difficulties with censorship issues. It is said that Howard Hughes had finally had enough, and released the film in 1932 without censor approval. Interestingly, in my opinion, Scarface is the most sophisticated and realistic of the Big Three, with characters more 3-dimensional than the other two. The look and sound of Scarface was better as well, although it had been filmed before either of the other two.

Little Caesar

Caesar Enrico Bandello was the first of the classic gangsters to hit the screen. Edward G. Robinson strutted into view and was given the name Little Caesar by a mob leader who meant it disparagingly. But we know better – Rico was born to murder and bully his way to the top, earning his title as most of the Roman Caesars did. Rico brought with him a friend who had done his share of robberies and shootings, Joe Massara, played by Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. Robinson was 38 years old at the time, and Fairbanks only 23 and very handsome. Robinson said of himself, “Some people have youth, some beauty – I have menace.” Few movie gangsters are as menacing as Rico. To me, Rico is the least likeable of the Big Three. It isn’t just because of Robinson’s famous mannerisms, the sneer, his sarcastic “Yeah! See? Yeah!” Rico is a killing machine, never swerving from his path to the top. He hesitates only once in his murderous rise, and that involves his friend, Joe.

|

| Olga (Glenda Farrell) and Joe (Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.) |

|

| The great Edward G. |

Public Enemy

Tom Powers was introduced to viewers just three months after Rico met his death behind a billboard. James Cagney, at the age of 32, had originally been hired to play Matt Doyle, childhood friend, with Edward Woods as Tom. However, director William Wellman saw Cagney’s potential and switched the two. Tom Powers was as different from Rico as fish from fowl. Tom needed women, all types, all sizes, all ages. Tom is more likeable than Rico, although just as brutal and without sense of morality. We see Tom as a bad young boy whose father had a heavy hand with the razor strap when Tom was too bad. His mother (Beryl Mercer), on the other hand, is a nervous little pudding of a woman who can’t see any bad in her boy. Tom’s brother Mike (Donald Cook) takes the high road to education and decency. Tom’s descent into crime is helped along by seedy adults more than happy to take advantage of his natural tendencies to steal and bully. Tom and Matt grow up together to become partners in crime. Matt is always second banana to Tom, not as hard or ambitious, but always at Tom’s heel like a faithful puppy. Matt wants a more normal life, and he meets and marries Mamie (Joan Blondell), a girl perhaps a little off-color, but basically a good girl.

|

| The famous grapefruit scene |

|

| Cagney on set, waiting to film the ambush scene! |

|

| Eddie (Cagney and Gwen (Harlow) |

|

| Eddie with brother Mike (Donald Wood) and Mother (Beryl Mercer) |

Tom: So beer ain't good enough for you, huh?

Mike: Do you think I care if there was just beer in that keg? I know what's in it. I know what you've been doing all this time, how you got those clothes and those new cars. You've been telling Ma that you've gone into politics that you're on the city payroll. Pat Burke told me everything. You murderers! There's not only beer in that jug. There's beer and blood - blood of men!

Tom: You ain't changed a bit. Besides, your hands ain't so clean. You killed and liked it. You didn't get them medals for holding hands with them Germans.

|

| "I ain't so tough." |

As with Edward G. Robinson, Cagney’s success as a bad guy was also unexpected. He too was a very gentle man who loved the country, preferred song-and-dance parts, and wanted nothing to do with the Hollywood scene. One of the nicest anecdotes about Cagney tells that he would often leave early, claiming he was too ill to do any more shooting. This was to ensure an extra day of filming so the underpaid crew and extras could get additional salary. Can you see Tom Powers doing that? I don’t think so

|

| Tony Camonte (Paul Muni) with his "Chicago typewriter" |

Tony Camonte was the third gangster big-shot to hit the screen and to me, he was the most realistic and frightening of the Big Three. While Rico was based upon Chicago mobster Salvatore Cardinella, and Tom Powers was inspired by Irish gangster boss Dean O’Bannion, Tony Camonte is 100% Al Capone. Capone was indicted for tax fraud and sentenced to prison in early 1932. Scarface was released April 9th of that year, and Capone did not report to prison until May. Capone saw the movie and loved it. Capone may have been good at bootlegging and murder, but he was not a very bright guy. The great Paul Muni, 36 years old at the time, makes him look like a murderous ape, an ignorant man who thinks he is smart and whistles an opera tune when he kills, a man who carries incestuous lust for his own sister, and who ends up yellow, begging for his life. I can’t imagine being thrilled to be portrayed like that, but then who can know what a man like Capone has in his head.

|

| Guino (George Raft) flipping the coin |

|

| Cesca (beautiful Ann Dvorak) |

Cesca and Guino fall in love. They keep it a secret from Tony because of Guino’s fears of Tony’s reaction. While Tony is away, they marry and decide to surprise him. Tony finds Guino in Cesca’s apartment before he knows this, and he shoots Guino to death. Cesca is devastated and terrified of her brother. Strangely, though, she goes to him in his final shoot-out with police to kill him herself, but ends up telling him “You’re me, I’m you, it’s always been that way.” Perhaps Cesca has harbored forbidden feelings for Tony as well. Just as their mother predicted, Tony does not try to save Cesca by sending her away. He is happy that she wants to fight it out with him. When Cesca is killed by police bullets, Tony finally realizes that he has lost Guino, Cesca, Poppy, even his toady Angelo. He stumbles about calling their names in the tear gas-filled room, staggers out to meet the police, pleading for his life, tries to run and is cut down in a a hail of bullets.

In my opinion, Scarface is the best of the Big Three. The only flaw I can see in the movie is the character of Angelo, played by vaudeville comedian Vince Barnett. Angelo is Tony’s toady, and to me the character is extremely annoying in the attempt at comic relief. Perhaps the filmmakers thought it would distract viewers from the constant violence and sound of tommyguns, but it doesn’t work that way and is just irritating.

Like Cagney and Robinson, Paul Muni was not a bad-guy type. He was never typecast as a gangster, unlike the other two. Muni played parts in many genres, famous for his ability to change his looks and accent to inhabit a role. For Scarface, he wore lifts in his shoes to add 3-4 inches, as well as padding so that he would appear more hulking and menacing. Of himself, despite his superstar status, Muni said “I’m an actor…a journeyman actor. I think ‘star’ is what you call actors who can’t act.” In an unusually generous tribute from one movie star to another, Muni described Robert Donat’s performance in Goodbye, Mr. Chips as “…the most magnificent performance I’ve ever seen on any screen…he is the greatest actor we have today.” Very nice man.

PART TWO

Prologue

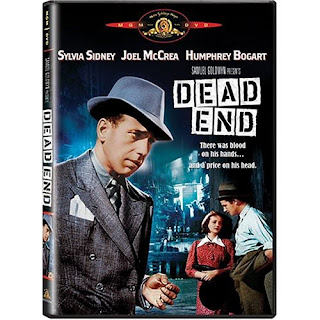

The first gangster films were the seminal blueprint for those to come. By the late 1930’s, the gangster movie formula as highlighted in the series prologue had been perfected. By this time, the bad guys had evolved from sociopathic thugs without conscience to criminals who, for the most part, had started life as normal people for whom bad luck and desperate circumstances were the causes for turning to a life of crime. Because of this depiction of the criminal, audiences found themselves feeling sympathy and understanding despite the gangsters’ same basic appetites for money and power that resulted in murder and social chaos. I have chosen three movies of the late 30’s to spotlight this important modification in the image of the villain in movies: Dead End (1937) with Humphrey Bogart, Angels With Dirty Faces (1938) and The Roaring Twenties (1939), both with James Cagney.

Dead End

Adapted from a Broadway play, Dead End was produced by United Artists. Director William Wyler and set designer Richard Day created a slum neighborhood so realistic that New York natives recognized it as a real part of the city. A posh apartment building surrounded by a wall looks down on a poverty-stricken area of struggling people trying to survive day to day. The movie takes place in a 24-hour period, weaving several stories into a tapestry of differing dreams, despondency and hopes. The cast is spectacular – Humphrey Bogart, Sylvia Sidney, Joel McCrea, Claire Trevor, Allen Jenkins, Marjorie Main and the Dead End kids. For our purposes, we will concentrate on the story of Baby Face Martin as portrayed by Bogart.

Adapted from a Broadway play, Dead End was produced by United Artists. Director William Wyler and set designer Richard Day created a slum neighborhood so realistic that New York natives recognized it as a real part of the city. A posh apartment building surrounded by a wall looks down on a poverty-stricken area of struggling people trying to survive day to day. The movie takes place in a 24-hour period, weaving several stories into a tapestry of differing dreams, despondency and hopes. The cast is spectacular – Humphrey Bogart, Sylvia Sidney, Joel McCrea, Claire Trevor, Allen Jenkins, Marjorie Main and the Dead End kids. For our purposes, we will concentrate on the story of Baby Face Martin as portrayed by Bogart.

Bogart was 34 years old at this time, and Dead End was his first portrayal of a serious mobster of some depth. His earlier roles had been limited to the rather spineless lesser member of criminal gangs. Even after Dead End, he was again relegated to that type, as we will see in Angels With Dirty Faces and The Roaring Twenties. However, in Dead End we see the future Bogart legend in its early development.

The story of Baby Face Martin reminds me of a famous literary quote: “You can’t go home again.” Wanted by the law, even having changed his face with plastic surgery, Baby Face is drawn to his old neighborhood and the need to reconnect with his mother and his first love, who in his mind are still the same. Baby Face’s loyal friend Hunk, portrayed by the wonderful character actor Allen Jenkins, acts as the voice of realism. Hunk knows that it is foolish of Baby Face to return to the home base, and also that nothing would be accomplished for Baby Face but disappointment and pain. However, his boss refuses to listen. Something in Baby Face desperately desires to go back to his youth, when he had love and hope.

|

| Ma Martin (Marjorie Main) |

The Dead End kids, slum boys with no male figure to help them develop into decent men, are impressed by Baby Face and his charismatic tough guy reputation. Baby Face revels in their hero worship which feeds his ego and gives rationale to his life of crime. But this is not enough for him. He wants to see his mother again, and finds her in the foyer of the tenement in which he grew up. He is like a happy boy as he runs up to his mother crying “Ma, Ma…it’s me. I had my face changed a little, but it’s me!” Ma, played beautifully by Marjorie Main, is a woman overwhelmed by the despair and defeat that has ruined her life, especially where her son is concerned. Ma’s reaction to her son’s visit is shocking. “You no-good tramp. You dirty old dog.” Baby Face is stunned. “It’s been 10 years, Ma. Ain’t you glad to see me, Ma?” Ma is not glad to see him. She slaps him hard across the face and slowly climbs the stairs, reciting like a litany the sorrows her criminal son has brought to her. With tears and revulsion in her face, Ma says “Why don’t you leave me be? Why don’t you go away and die?” Baby Face is devastated, his face full of pain. He returns to the bar where Hunk is waiting and puts his face in his hands. It is a heartbreaking scene.

|

| Baby Face and Francey (Claire Trevor) |

There is one more hope for Baby Face – his first love, Francey. The marvelous Claire Trevor spends only about 5 minutes on screen, but the scene between Francey and Baby Face is unforgettable. Baby Face has no right to place himself above anyone after the violent life he has led, but he cannot accept or sympathize with the appalling truth he learns about Francey's desperate life as a prostitute. He expected the innocent young girl he left behind many years before, and perhaps her own fate mirrored his own too closely. Bogart and Trevor play this scene with the undeniable acting gifts with which each was blessed. Although the original play made no bones about the fact that Francey has syphilis, the movie code allowed only a hint of the reason for Francey's condition. Once again powerless to have stopped his boss from more grief, Hunk tells him “We all make mistakes, boss. That’s why they put rubber on the end of pencils…..never go back, always go forward….where you go, I go.” If nothing else, Baby Face had one unwavering friend in Hunk. Baby Face is bad, no doubt about that, but he is also a pitiable character for whom audiences feel sorrow and sympathy.

Angels With Dirty Faces

In my opinion the best of this decade’s gangster movies, Angels With Dirty Faces has everything – James Cagney as Rocky Sullivan, the most captivating and magnetic of gangsters; Pat O’Brien as Fr. Jerry Connolly, the childhood friend who became a priest; the Dead End kids once again, this time as Cagney’s awestruck disciples; Bogart as James Frazier, Cagney’s backstabbing crime partner; and Ann Sheridan as Laury Ferguson, the street-wise but good girl who loves Rocky. Directed by Michael Curtiz, it is the Warner Brothers gangster formula at its best. As an interesting aside, the Dead End Kids were difficult to handle during filming. Their behavior was chaotic, ad-libbing lines and even destroying props. Cagney, normally a laid-back man, finally had enough and popped Leo Gorcey in the nose. The chaos ended.

In my opinion the best of this decade’s gangster movies, Angels With Dirty Faces has everything – James Cagney as Rocky Sullivan, the most captivating and magnetic of gangsters; Pat O’Brien as Fr. Jerry Connolly, the childhood friend who became a priest; the Dead End kids once again, this time as Cagney’s awestruck disciples; Bogart as James Frazier, Cagney’s backstabbing crime partner; and Ann Sheridan as Laury Ferguson, the street-wise but good girl who loves Rocky. Directed by Michael Curtiz, it is the Warner Brothers gangster formula at its best. As an interesting aside, the Dead End Kids were difficult to handle during filming. Their behavior was chaotic, ad-libbing lines and even destroying props. Cagney, normally a laid-back man, finally had enough and popped Leo Gorcey in the nose. The chaos ended.

As young boys, Rocky and Jerry are kids of the slums, wayward and not above a little stealing, but basically decent growing up in such conditions. During one escapade, Rocky and Jerry try to steal fountain pens from a freight car. Railroad bulls give chase, and Jerry falls onto tracks with a train bearing down upon him. Rocky runs back and saves him. The boys climb a fence to get away – Jerry makes it over, but Rocky is caught. This sets the stage for the divergent paths of the two friends. Rocky is sent to reform school, is influenced by criminals and starts a life of crime. Jerry goes on to be educated and becomes a priest.

|

| Rocky Sullivan (James Cagney) and old friend Father Jerry (Pat O'Brien) |

|

| Rocky and the gang |

Rocky’s charismatic personality endears him to the Dead End kids and his childhood friend Laury. In a wonderfully humorous scene where Rocky and Fr. Jerry try to teach the boys to play basketball by the rules, Rocky trips them up and slaps them around when they bully the other team. Accustomed to that kind of treatment, the boys do not feel abused. They understand his technique and admire him even more. Fr. Jerry tells Laurie that he believes Rocky could be straightened out. But it is not to be. Ann Sheridan’s role as Laury is minimal and rather low-key. Perhaps this is because the main focus of the movie is the friendship between Rocky and Fr. Jerry.

Rocky’s motto is “Don’t be a sucker”, and he proves that by threatening his former lawyer and crime partner, James Frazier, with violence if money promised to Rocky is not paid. Frazier, scared and mopping his brow, pretends that he has every intention to pay Rocky. However, he and the big boss, played by character actor George Bancroft, plan to have Rocky knocked off. Fr. Jerry, despite his love for Rocky, is determined to save his boys from emulating gangsters and begins a public campaign to bring down the criminal element, including Rocky, Frazier and the boss. Frazier and the boss plan to kill Fr. Jerry as well as Rocky, but Rocky hears their plan. He shoots the boss, then kills Frazier as Frazier cowers and begs for his life.

|

| Rocky takes Fr. Jerry hostage |

Thus begins Rocky’s last stand as he is chased by police and takes refuge in a warehouse, for a standoff that reveals his true dangerous side. In a shooting spree during which everyone seems to have an endless supply of bullets, Rocky kills several policemen. Tear gas is lobbed into the warehouse. Fr. Jerry and Laury come to the scene, and Fr. Jerry insists that he be allowed to talk to Rocky. He enters the building and tries to talk Rocky into surrendering. Instead, Rocky uses Fr. Jerry as a shield, and leaves the building threatening to shoot him in the head. Rocky says “Duck, Jerry”, pushes his friend away, and runs down a blind alley. He is trapped by police. One officer finds that Rocky’s gun has no bullets. “Empty,” he says. Defiantly, Rocky sneers “So is your thick skull, copper.”

|

| Walking the Last Mile |

Condemned to death in the electric chair, Rocky is still a hero to the gang of boys, who believe he will go out laughing and heroic. Fr. Jerry comes to Rocky on the day of his execution and asks if he is afraid. Rocky answers “To be afraid, you gotta have a heart. I don’t think I got one”. Fr. Jerry then asks the ultimate favor of Rocky, to act like a coward as he goes to his death. He wants the boys to be ashamed of Rocky, and lose the hero worship they have felt for him. Rocky refuses to shame himself like that, and says no vehemently. Fr. Jerry accompanies Rocky on one of the best-filmed last-mile scenes, asking him again to do this for the boys, but Rocky rebuffs him again. The two men say goodbye, Rocky asking Fr. Jerry not to let him hear the priest’s prayers. Fr. Jerry answers “I promise you won’t hear me.” Rocky is taken in to the electric chair. Suddenly he begins to cry and plead to be let go. He tries to grab onto anything he can find, making the guards pull and force him into the chair. Rocky continues to cry and beg until the electricity kills him. Fr. Jerry looks to heaven and cries his own tears of gratitude.

The boys refuse to believe the headlines that announce the tough guy’s cowardice. Fr. Jerry comes to them, and tells them that it was true. He died as they said. The devastated boys have lost their admiration for Rocky. Fr. Jerry says “All right fellas. Let’s go and say a prayer for a boy who couldn’t run as fast as I could.” Cagney would never reveal whether or not he believed Rocky died a true coward or found the courage and caring heart to let the boys feel shame and disappointment as Fr. Jerry wanted. Once again, though Rocky was a ruthless killer, we like him, believe in a basic goodness, and mourn his fate.

The Roaring Twenties

Another WB production, directed by Raoul Walsh, The Roaring Twenties is a nostalgic picture of an era. During the credits, the words of writer Mark Hellinger are displayed, summing up his feeling about the story: "It may come to pass that, at some distant date, we will be confronted with another period similar to the one depicted in this photoplay. If that happens, I pray that the events, as dramatized here, will be remembered. In this film, the characters are composites of people I knew, and the situations are those that actually occurred. Bitter or sweet, most memories become precious as the years move on. This film is a memory - and I am grateful for it."

The Roaring Twenties is a most unusual gangster film. Documentary scenes set the stage for the history of the era before and during Prohibition. Cagney as Eddie Bartlett is not a ruthless killer, but a man forced into crime against his will. Eddie first meets George Hally (Bogart) and Lloyd Hart (Jeffrey Lynn) in a trench during a horrific battle in World War I. Hally plans to go back to his former life as a bootlegger, but Eddie’s dream is to return to his job as a garage mechanic and work toward having his own business. Lloyd wants to be a lawyer. The men survive the war and go their different ways. Eddie returns to the States to find that his job is gone, another man who had not gone to war having taken his place. He returns to his old friend Danny Green (the wonderful Frank McHugh), and tries to find a job. His only option is to share a job driving a cab with Danny. Eventually, Eddie finds himself in the bootlegging business to make something out of himself. Danny is a true friend, and trustingly follows Eddie into the business. Lloyd becomes Eddie’s lawyer, and George becomes a business partner with Eddie.

Another WB production, directed by Raoul Walsh, The Roaring Twenties is a nostalgic picture of an era. During the credits, the words of writer Mark Hellinger are displayed, summing up his feeling about the story: "It may come to pass that, at some distant date, we will be confronted with another period similar to the one depicted in this photoplay. If that happens, I pray that the events, as dramatized here, will be remembered. In this film, the characters are composites of people I knew, and the situations are those that actually occurred. Bitter or sweet, most memories become precious as the years move on. This film is a memory - and I am grateful for it."

The Roaring Twenties is a most unusual gangster film. Documentary scenes set the stage for the history of the era before and during Prohibition. Cagney as Eddie Bartlett is not a ruthless killer, but a man forced into crime against his will. Eddie first meets George Hally (Bogart) and Lloyd Hart (Jeffrey Lynn) in a trench during a horrific battle in World War I. Hally plans to go back to his former life as a bootlegger, but Eddie’s dream is to return to his job as a garage mechanic and work toward having his own business. Lloyd wants to be a lawyer. The men survive the war and go their different ways. Eddie returns to the States to find that his job is gone, another man who had not gone to war having taken his place. He returns to his old friend Danny Green (the wonderful Frank McHugh), and tries to find a job. His only option is to share a job driving a cab with Danny. Eventually, Eddie finds himself in the bootlegging business to make something out of himself. Danny is a true friend, and trustingly follows Eddie into the business. Lloyd becomes Eddie’s lawyer, and George becomes a business partner with Eddie.

|

| Danny Green (Frank McHugh) and Eddie Bartlett (James Cagney) |

|

| Lloyd Hart (Jeffrey Lynn), Jean Sherman (Priscilla Lane) and Eddie |

Eddie flourishes in the bootlegging business and becomes a top man in town. As in many of the Warner Brothers movies, a beautiful young girl comes into Eddie’s life. Jean Sherman (Priscilla Lane) is a girl from a good family who wants to be a singer. Eddie gives her a break by hiring her to sing in his nightclub. Priscilla Lane as Jean is naïve and cute as a bug in this part, and sings some of the favorite songs from that era, “I’m Just Wild About Harry” and “Melancholy Baby.” Eddie falls in love with her and Jean allows the relationship to grow, unsure of her feelings for Eddie. When Eddie asks Jean to marry him, she realizes that she is not in love with him. It becomes clear that Jean and Lloyd have fallen in love and want to marry. Eddie is distraught at losing Jean, but takes it with good grace. Lloyd also wants to leave the business and be a respectable lawyer. George is distrustful of the knowledge Lloyd has about their bootlegging business, but Eddie warns him to leave the couple alone.

|

| Eddie and Panama (Gladys George) |

Another important woman in Eddie’s life is Panama Smith (the great Gladys George), a nightclub hostess. Based on the real-life nightclub hostess Texas Guinan, Panama used to be popular and successful, but she is getting older and past her prime. Panama is Eddie’s friend and shoulder to lean on, but she is also in love with him. He carries his love for Jean in his heart, and does not return Panama’s love. That does not deter her from always being there for Eddie when he needs her.

The disastrous fall of the stock market on Black Tuesday, October 19, 1929, destroys Eddie’s fortune. The end of Prohibition causes the bootlegging business to disappear. Eddie has lost his dear friend Danny in a gang shootout. He is a ruined man. He begins to drink heavily, and Panama does her best to make him dry up and find a way to make a living. Eddie goes back to cab driving, and one day unknowingly finds that Jean is a passenger. He is still hurt about losing her, but Jean asks him to come into the house and visit with her. Jean and Lloyd now have a 4-year old child. Eddie, though sad that he missed out on a happy home life, wistfully admires the family that Jean and Lloyd have built.

|

| George Halley (Humphrey Bogart) and Eddie face-to-face |

George, who unlike Eddie has continued his life as a criminal, finds out about Lloyd’s rise in the district attorney’s office, and plans to kill him because of the chance that Lloyd will use his knowledge of George’s illegal activities. Down-and-out Eddie learns of the plan, and goes to George’s office. Eddie is now a laughable figure to the well-off George, who feels contempt for Eddie’s protectiveness of Jean and her family. Eddie picks up a gun – he has never been a killer type, but feels that he has no choice. George begs Eddie not to shoot him, but Eddie kills him.

|

| "He used to be a big shot." |

Out on the street, Eddie is shot in the back by one of George’s cohorts. Panama has followed Eddie, and sees him stagger down the street toward the steps of a church. He dies on the steps, with Panama holding him in her arms. In one of classic film's most famous endings, a policeman arrives, pulls out his notebook, and asks Panama “Who is he?” “Eddie Bartlett.” “What was his business?” “He used to be a big shot.” The Roaring Twenties presents us with a truly sympathetic character in Eddie. A good man who was forced to go bad, a loving man who gave his life for his friends, Eddie is not really a gangster. He is a tragic figure.

***************************************************************************

PART THREE

Prologue

This, the final installment in my series, centers on three movies that proved to be the end of the era of classic gangster films. For this purpose, I have chosen three great Warner Brothers productions, High Sierra, Key Largo and White Heat. Each spotlights the most legendary actors of this genre, Humphrey Bogart, Edward G. Robinson and James Cagney. These three movies reflect the changes in the classic formula, so ingeniously created by Warner Brothers, for characters in the gangster genre. Gone are the two major types of mobster pals typical to the 1930's. The women in the lives of the gangsters no longer fit the stereotypes as discussed in Part One. See my prologue in Part One for a brief summary of the purpose and historical basis in spotlighting my focus on the relationships of the movie mobster to his friends and women. *Because of the requirements of discussion on this topic, there are *Spoilers* within the reviews.*

High Sierra

Celebrated as the movie that made Humphrey Bogart a star, High Sierra is considered by some to be the last of the great classic gangster films. This is true to a certain extent, but as you will see in my assessment of White Heat, I believe it was only by date of release that High Sierra could be regarded as such. Released by Warner Brothers in 1941, and directed by Raoul Walsh, High Sierra was the fortunate cause, by default, for Bogart’s stardom. Paul Muni of Scarface fame was first considered, but Muni was not interested. George Raft was the next choice, but turned it down. Raft wanted to change his image, was cannily steered away from the role by Bogart; Raft did not want to play an older gangster who is killed in the end. After lobbying by Bogart, he was cast as “Mad Dog” Roy Earle.

Celebrated as the movie that made Humphrey Bogart a star, High Sierra is considered by some to be the last of the great classic gangster films. This is true to a certain extent, but as you will see in my assessment of White Heat, I believe it was only by date of release that High Sierra could be regarded as such. Released by Warner Brothers in 1941, and directed by Raoul Walsh, High Sierra was the fortunate cause, by default, for Bogart’s stardom. Paul Muni of Scarface fame was first considered, but Muni was not interested. George Raft was the next choice, but turned it down. Raft wanted to change his image, was cannily steered away from the role by Bogart; Raft did not want to play an older gangster who is killed in the end. After lobbying by Bogart, he was cast as “Mad Dog” Roy Earle.

|

| Marie (Ida Lupino), Red (Arthur Kennedy), Babe (Alan Curtis) and Humphrey Bogart (Roy Earle) |

|

| Roy, Marie and Pard (Zero) |

Two women who symbolize in some respects the Warner Brothers formula for gangster films play an essential part in Roy’s life. Marie (the beautiful Ida Lupino) is a girl who has never gotten a break, who has tried to crash out of her own desolate fate all of her life. Marie is tough in order to protect herself from life, but she is good at heart. She loves Roy and wants to be with him in whatever he does. But Roy is smitten with a crippled young farm girl, Velma (Joan Leslie), whom he met with her family on the road to California. Velma’s Pa (Henry Travers) is unaware of Roy’s criminal life, but he sees a basic decency in him and hopes that through Velma, Roy will be part of the family. Roy brings in Doc to see if Velma’s club foot can be corrected, and he pays for her operation. Doc sees Roy’s longing for Velma, and advises Roy to forget her. “You need a high-steppin’ filly who can keep up with you….remember what Johnny Dillinger said? Guys like you were rushing toward death, just rushing toward death.” Roy is deaf to Doc’s warning. Velma proves to be dishonest with Roy, letting him open his heart and his wallet for her while knowing she wants another man. She turns Roy down when he asks to marry her. Her rejection is very hurtful to Roy, and he also feels the loss of a deeply-felt dream of the simple life he grew up with on the Indiana farm.

|

| Velma (Joan Leslie) |

|

| Marie and Roy |

? < Bad Girl/Good Girl > ?

In this way, the two women are actually reversed in their roles. Velma is the deceitful one for whom we feel contempt and anger. It is actually Marie who is honest and loving, which Roy finally realizes. He falls in love with Marie and finds real happiness with her. When Roy and Marie have a fight, Marie feels badly about yelling at him. Roy says with a smile, “I like it! That’s the way married people oughta act!” But it is too late for Roy now. Because of the bungled robbery with the two young men, and Roy’s self-defensive shooting of a crooked cop, he is dubbed unfairly as Public Enemy No.1. Roy sends the heartbroken Marie away for while to protect her while he runs from the police. In one of the most spine-tingling and poignant endings to a gangster movie, Roy is trapped in the High Sierras, taking refuge in the mountains to escape police. Among cold, bleak rocks, Roy makes his last stand. Unable to get to Roy, the police send a sharpshooter to climb above Roy’s hiding place.

? < Bad Girl/Good Girl > ?

In this way, the two women are actually reversed in their roles. Velma is the deceitful one for whom we feel contempt and anger. It is actually Marie who is honest and loving, which Roy finally realizes. He falls in love with Marie and finds real happiness with her. When Roy and Marie have a fight, Marie feels badly about yelling at him. Roy says with a smile, “I like it! That’s the way married people oughta act!” But it is too late for Roy now. Because of the bungled robbery with the two young men, and Roy’s self-defensive shooting of a crooked cop, he is dubbed unfairly as Public Enemy No.1. Roy sends the heartbroken Marie away for while to protect her while he runs from the police. In one of the most spine-tingling and poignant endings to a gangster movie, Roy is trapped in the High Sierras, taking refuge in the mountains to escape police. Among cold, bleak rocks, Roy makes his last stand. Unable to get to Roy, the police send a sharpshooter to climb above Roy’s hiding place.

|

| Roy trapped in the High Sierras |

Key Largo

Key Largo is a textbook representation of the transformation of the gangster image brought about after World War II. Released in 1948, directed by John Huston, the movie illustrates a significant change in audience views. America had suffered under real monsters, Adolph Hitler of the Third Reich and Hirohito of the Empire of Japan. Movie audiences had lost the naïve admiration of movie gangsters in the 1930’s. It was no longer possible to feel empathy for men whose motives were too similar in their merciless appetite for power and control.

|

| Nora Temple (Lauren Bacall) and Frank McCloud (Humphrey Bogart) |

|

| Mr. Temple (Lionel Barrymore) telling about the great hurricane |

In a much more sophisticated manner than Little Caesar 17 years before, Edward G. Robinson is again a killer without conscience for which no empathy is possible. Unlike Little Caesar, Johnny Rocco has women in his life, and his cruelty to them is abhorrent. There are several levels to Key Largo’s story, all brought together with the arrival of a devastating hurricane – Frank McCloud (Humphrey Bogart) as the war-weary and disillusioned man who just can’t do combat with evil anymore …”I believed some words…(but now) I fight nobody’s battles but mine… one Rocco more or less isn’t worth dying for.”; Nora Temple (Lauren Bacall) as the war widow who can’t understand Frank’s attitude … “When you believed like George did, dying didn’t seem to matter…If I felt like you, I’d want to be dead too.”; James Temple (Lionel Barrymore), a crippled but strong-minded man whose son George was killed in the war, and has no fear of angering Rocco with his contempt … “You filth …You don’t like it, do you Rocco, the storm. Show it your gun … if it doesn’t stop, shoot it!”; Gaye Dawn (Claire Trevor) as the aging, drunken nightclub singer clinging to the increasingly scornful and disinterested Rocco … “Gee, honey, you’re awful mean to me.” The focus of this series is the gangster, and it is Edward G. Robinson’s character that will be highlighted.

|

| Johnny Rocco (Edward G. Robinson) with Nora and Frank |

One of the scenes between Rocco and Nora is significant in demonstrating the difference between the early era and the post-war gangsters. Rocco steps up to Nora and whispers in her ear. Her face shows us that he is suggesting filthy sexual acts. Nora steps away. Rocco again whispers in her ear, and she turns and spits in his face. His rage is frightening, and he wants to kill Nora, but Frank turns his attention aside. Mobsters always had women and treated them badly, but we had never seen the truly disgusting side of their nature until now. There is no possibility for any kind of respect for Rocco after this unsettling scene.

|

| Rocco and Gaye Dawn (Claire Trevor) |

|

| Rocco shows his true cowardice |

Rocco’s cowardly fear of the hurricane, as well as his fear of Bogart’s complete control over his fate in the final scene of Key Largo, are the final evidence of his repulsive character. As in Little Caesar, Rocco cannot believe he will die, since to him the world only exists for his wants and desires. Edward G. Robinson’s performance in this movie is phenomenal. Key Largo is an essential film in the post-war gangster movie genre.

Released in 1949, directed by Raoul Walsh, White Heat is James Cagney’s swan song as the ultimate gangster. Cagney was 50 years old at this time, but fast-talking and energetic, still using his famous mannerisms even better than before, drawing upon depth and sophistication. In my opinion, it is also his greatest and most flawless performance. During the 30’s and 40’s, gangster films were snubbed by the Oscars, and no performance was as unfairly ignored as Cagney’s role as Cody Jarrett in White Heat. As I mentioned in the above review of High Sierra, I believe that White Heat is actually the last of the golden era of gangster films. Although part of the movie is devoted to modern police technology, it is very similar to films of the late 30’s. We find ourselves back to a story about a man who is admittedly a sociopathic killer, but who is also mentally ill and elicits sympathy. And of course there is Cagney – it’s almost impossible not to like him no matter who he plays.

|

| Cody munches on a chicken leg and shoots a man |

|

| Cody and Vic Pardo (Edmund O'Brien) |

In the beginning, Cody has no male friends. His group of followers, including Big Ed (Steve Cochran), obey him not only because he is the best at crime, but also because he scares most of them to death. Not Big Ed, though. Big Ed is a handsome young man who has big ambitions for himself. He also has a yen for Cody’s wife, Verna (bombshell Virginia Mayo) which is just fine with Verna. But Cody is sharp as a tack. He is well aware of Ed’s thinking. Cody stares Big Ed down and says “You know something Verna? If I turned my back long enough for Big Ed to put a hole in it, there’d be a hole in it.” Cody meets a young fellow inmate while in prison, Vic Pardo (Edmond O’Brien). Vic makes efforts to befriend him. Cody, at first angry and distrustful, comes to like Vic. He talks to Vic in their cell, and eventually takes him into his trust, a previously unheard of vulnerability for Cody. Only the audience knows that Vic Pardo is actually a police detective operating under an alias. Vic has been planted in the prison to get close to Cody and find evidence of crimes they have not been able to pin on him. Vic is finally able to obtain Cody’s trust when he helps him with one of Cody’s dangerous weaknesses – debilitating migraine headaches.

|

| Cody and Verna Jarrett (Virginia Mayo) |

|

| Cody and Ma Jarrett (Margaret Wycherly) |

|

| Ma plans to knock off Big Ed |

|

| "Made it, Ma! Top of the world!" |

My sincere thanks to the loyal readers who have followed my gangster series. I loved writing it, and I hope you enjoyed it. Just for fun, I’m posting below some candid photos of the wonderful actors who made us believe for a while that they really were gangsters.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)